I

Back in the 80s, I worked with Mike, who had strong opinions on classical music. He complained whenever Boccherini came on the radio: “The epitome of empty note spinning!” When a Tchaikovsky piece went into a long final inning, he’d yell at the radio, “Oh, finish it already!” He stood for high standards. He didn’t think Ravel would make it into the long-term classical canon, or Prokofiev, or Rachmaninoff, or Gershwin, or even Stravinsky (who he loved). I asked him, what 20th century piece would make it? He thought a moment.

And he told me about the Berg Violin Concerto.

II

Alban Berg (1885–1935), Viennese, fathered an illegitimate child in his teens as part of his first big romance, with a married woman named Marie, whose nickname was Mizzi. He attempted suicide, failed, then settled down after meeting the woman he would marry. A student of Schönberg, he wrote atonal and 12-tone music, including two operas (one unfinished). Unlike Schönberg, he wrote melodic music with a wide palette of emotional affect. The Nazis went after him as part of their “Degenerate Music” [Entartete Musik] pogrom, probably because of his association with Schönberg.

In January of 1935, the Russian-American violinist Louis Krasner met Berg and asked him to write a violin concerto for him. Berg, who didn’t want to be bothered with a showpiece, resisted, but Krasner persisted, arguing that he could write a piece with beauty, “demolishing the antagonism of the ‘cerebral, no emotion’ cliché.” Berg finally agreed, though he went on working on his second opera, Lulu, paying little attention to his commission.

In April of 1935, Manon Gropius, daughter of Walter Gropius and Alma Mahler Gropius (and who was much loved by the artists and musicians who surrounded Alma) died of polio at the age of 18. Berg asked Alma if he could dedicate the piece “to the memory of an angel” (the score’s subtitle), and began composing in earnest, putting his opera aside.

He had finished the skeleton of the piece on July 15, and on August 12 had finished its orchestration. “I never worked harder in my life,” he said, having basically written this concerto in six weeks.

III

A 12-tone piece, using a system based on Schönberg’s work in which the twelve notes of the chromatic scale are put into a specific order that forms the basis for thematic material as well as harmonic organization, the concerto is based upon a tone row that Berg created:

The twelve notes can be taken as four groups of three, and each group is made up of a major or minor triad. These are G minor, D major, A minor, and E major—G, D, A, and E are the open strings of a violin. The last four notes in the tone row make up the first four notes of a whole-tone scale. Berg uses all of this in his piece.

After a one-measure intro, the concerto opens with ‘open string’ arpeggios from the solo violin.

Berg seems to be calling attention to the instrument itself, but the piece doesn’t remain abstract for long. There are a number of developments, including a waltz and the quotation of a Carinthian folk song with the line “I would have overslept in Mizzi’s bed…”, making the piece partly autobiographical, in addition to being about Manon Gropius. The piece also seems autobiographical in the turbulence that develops, along with warlike drumbeats, as the world, especially Austria, went mad around Berg. About nineteen minutes into the piece, the clouds are dispelled and the music calms itself. Then comes a sort of miracle.

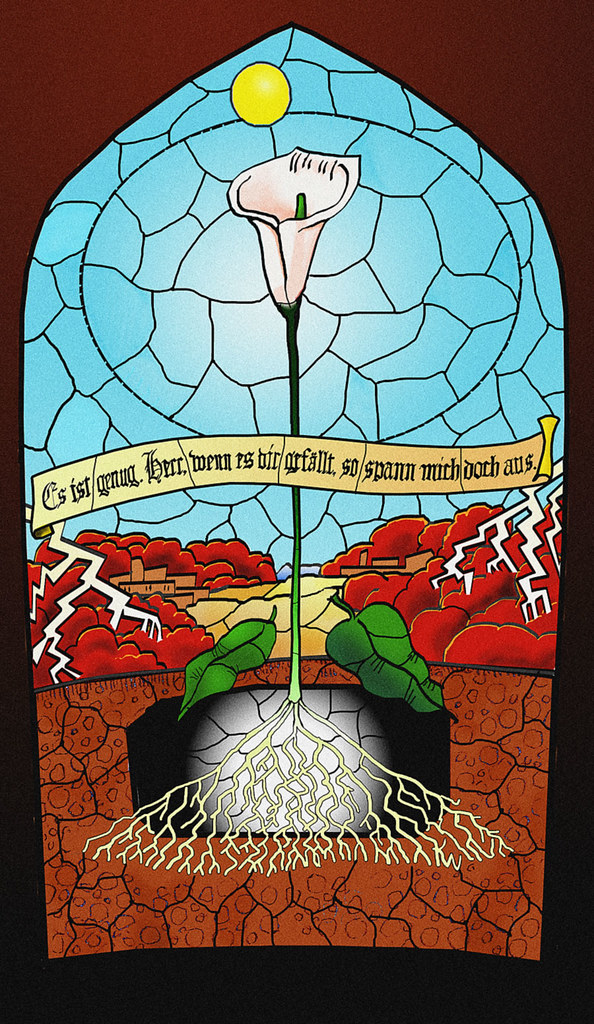

I remember Mike telling me: “Berg quotes a Bach chorale, and it fits right into his tone row.” The last four notes of the row, the whole-tone scale, are the first four notes of this almost unearthly (because of the four whole tones together) chorale melody used by Bach*. “Es ist genug. Herr, wenn es dir gefällt, so spanne mich doch aus.” “It is enough. Lord, when it pleases thee, then grant me release.” I stood before my classmates, presenting the artwork I based on this piece, trying not to choke up as I said these words.

The violin quotes the opening line, and wind instruments take up more of the chorale. The concerto goes on to finish with tranquil resignation, acceptance of fate and loss, and recaps the ‘open string’ figures from the start, with rising transpositions of the tone row, from bass to cello to viola to horn, and finally as the last statement from the solo violin, ending with a long, soft, high G that floats over the last notes of the orchestra like the first star of evening.

The violin quotes the opening line, and wind instruments take up more of the chorale. The concerto goes on to finish with tranquil resignation, acceptance of fate and loss, and recaps the ‘open string’ figures from the start, with rising transpositions of the tone row, from bass to cello to viola to horn, and finally as the last statement from the solo violin, ending with a long, soft, high G that floats over the last notes of the orchestra like the first star of evening.

IV

Berg died in December, 1935, without hearing his concerto performed. His opera, Lulu, had been finished in piano-vocal score, and he had orchestrated two of the three acts. On April 19, 1936, the concerto was premiered in Paris with Krasner as soloist. Viennese composer Anton Webern had been scheduled to conduct, but at the last minute, he was too emotionally distraught to go through with it. On the 18th, organizers of the concert prevailed upon conductor Hermann Scherchen, who was there for the event, to step in. He was given the score at 11:00 the night before, and had thirty minutes the next day to go over the piece with the musicians.

On May 1, 1936, Anton Webern and Louis Krasner played the British premiere of the piece with the BBC orchestra. A recording of the piece can be found at YouTube. I'm not sure why embedding doesn't work today, but the sound is very good, and this is as close to a definitive recording as I could imagine.

part 1

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aTYAm0BXkxs

part 2

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gKO-GKUgDXw

part 3

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3P7pz4aCNSk

part 4

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O59hMmE98Jw

V

For my final project in my fourth and last semester of music theory with John Reef at Nazareth College, I chose to make a stained-glass window (in Photoshop) based upon this piece. The above sections are based on the presentation I made before the class to lead (not a pun) up to it. The colors came from stained glass photos on the web. I lettered the scroll by hand on a graphics tablet with a will of its own. I should rework that sun, as the detail has vanished from it. Tried to make it plausible as a piece of glass-and-lead craftsmanship, though the roots strain credulity—they'd have to be painted on, I guess, like the in-ground and in-flower detail is intended to suggest. I roughened the texture on purpose, if you're wondering.

“Es ist genug. Herr, wenn es dir gefällt, so spanne mich doch aus.”

“It is enough. Lord, when it pleases thee, then grant me release.”

VI

An asteroid discovered in 1983 is now named Asteroid 4258 Berg, in honor of the composer.

.

.

.

footnote, from Wikipedia:

"Es ist genug" ("It is enough") is a German Lutheran hymn, with text by Franz Joachim Burmeister, written in 1662.[1] The melody, Zahn No. 7173,[2] was written by Johann Rudolf Ahle who collaborated with the poet. It begins with a sequence of three consecutive rising whole tone intervals.

.

For you music theory buffs, I calculate that the prime form of that asteroid would be (0236).

ReplyDeleteOver my head too often, as my musical ignorance is vast, and very nicely done. I printed this for Our Father who will appreciate it more intelligently than I. It will be a hard 93rd birthday card to top!

ReplyDeleteNice posts, Kip.

ReplyDeleteLooking forward to hearing the Berg one of these days.

Lovely stained glass window, too!

I'm so happy that you're writing your pieces. It was sweet, hearing your waltz the other day.